Carl Horn reflects on a superb manga that struggles for recognition.

Carl Horn reflects on a superb manga that struggles for recognition.

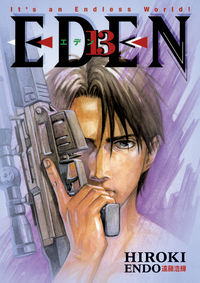

Naturally, I’m close to the manga I edit, but I don’t edit Eden: It’s an Endless World!; my friend Philip Simon does. Nor have I worked with its translator, Kumar Sivasubramanian. But I know the exceptional dedication they both have to Hiroki Endo’s Eden, and it’s not misplaced. Dark Horse has kept with this book for a reason. If as a fan you’ve ever asked yourself, “Where are the manga of today like Akira, Appleseed, or Ghost in the Shell?” the answer is here, with Eden, whose long-awaited volume 13 has just hit the stores.

And maybe you’re a little suspicious; those other titles don’t need any cheerleading, like I’m doing here. Years before the manga boom, Katsuhiro Otomo and Shirow Masamune earned their rep not only among manga readers but with crossover US comics fans as well. Before Dark Horse published it in its original black and white, a colorized Akira was released through Marvel’s Epic line, whereas DH’s Ghost in the Shell was the first manga ever to make the cover of Wizard (The “manga boom” is itself an increasingly nostalgic concept, although I raise an eyebrow like Spock to anyone who takes it to mean manga are over. I seem to recall the last “comics boom” ended way back in the 1990s, after all).

So if Eden deserves comparison to those classics, how come you’ve never heard of it? Format might play a role. Otomo and Shirow’s works were drawn in the right-to-left reading order common in Japan, but in the US they were published “flopped,” so that they could be read left to right. There’s no doubt this helps to reach crossover US comics fans (DH’s Blade of the Immortal is still published in this format, as are many manga pitched toward the comics-lit scene, such as Last Gasp’s Barefoot Gen, Drawn & Quarterly’s A Drifting Life, or Vertical’s Ayako). But Eden, per the creator’s request, is published in today’s common right-to-left format, which perhaps puts a barrier between it and those US comics fans that are open to manga, but are uncomfortable reading it Japanese style. Moreover, unlike Otomo or Shirow’s works, Eden is a shrink-wrapped title that comes with a “mature readers” label, something that often restricts the number of copies stores order (DH published an unedited, shrink-wrapped version of Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell in 2004, but this was long after it had found considerable success with its original, edited 1990s release).

I haven’t yet said much about Eden itself, have I? When I say it’s like the works of Otomo and Shirow, I definitely don’t mean that Hiroki Endo is simply imitating their art style or storytelling. Despite Eden’s unashamed elements of cyberpunk (if you’ve been missing jacked-in runners talking of ICE, or thugs with slit visors and fingers full of monofilament wire, Eden fills the void), it’s not a retro tribute to manga of the eighties and nineties—Eden is a contemporary expression. I mean that, like those earlier titles, Eden is a sprawling, cosmopolitan, postapocalyptic story of action, politics, and intrigue set on a future Earth (much of Eden takes place in urban South America) that’s still recognizably a descendant of our own, where a gruesome autoimmune disease called the Closure Virus has killed 15 percent of the population (rather than skeletons, the dead end up cracked shells of callused skin through which the internal organs leak out). That was a generation before the “now” of Eden—now, the virus has returned, in a dramatically altered form that may prove the final reckoning for the human species.

Eden takes place in the early years of the next century, but like the works of Otomo and Shirow, its politics seems to comment on current issues; the world of Eden resembles Thomas P. M. Barnett’s division of the world between the so-called “functioning core,” connected by globalization and backed by military power, and the “nonintegrating gap” where the core fights all its wars. The hero of Eden, Elijah Ballard, is a teenager whose parents were raised during the plague in the Eden of the title, a reserve in the US Virgin Islands isolated from the chaos. Born with antibodies against the Closure Virus, they left Eden, to know good and evil; particularly evil, as Elijah’s dad, Ennoia, becomes a South American drug lord at one end of the “gap,” dealing clear eyed in fear, cruelty, and degradation, but nevertheless aware that his power is one of the few remaining counterforces against a global system of ostensibly greater ideals, but equal ruthlessness.

Leaving behind a childhood of equal parts notoriety and privilege, Elijah starts to mature as he searches for his missing mother and sister. In Eden, this means the former private-school boy becomes a dangerous young man as he enters a world of gangsters, mercenaries, prostitutes, cops, spies, scientists, terrorists, hackers, and activists, the distinction between which is often unclear, and many of whom (because they are also all human beings) have their own ideas about their lives, what they mean, and why they will take other people’s. Endo certainly doesn’t believe that advancing science will reweave the twists put into us by our families, societies, and nations. No technology simply removes these things; look at any online comment thread to see just how unified instant global communications has made us. Of course, if we were obliged to speak to all those others we resent face to face, we might find ourselves more understanding of them, or we might find ourselves fighting them to the death—or, quite possibly, both. And that’s exactly the kind of journey Elijah makes in Eden: It’s an Endless World!