Naturally, I’m close to the manga I work on, but I don’t edit Hiroki Endo's Eden: It’s an Endless World!—my fellow editor Philip Simon does. Nor have I worked with its translator, Kumar Sivasubramanian. But I know the exceptional dedication they both have to Eden, and it’s not misplaced. We'll talk about vol. 14 of Eden next week, when it hits the stores, but first I'd like to tell you something about the series as a whole. If as a fan you’ve ever looked around at the manga in stores today and asked, “Whatever happened to the great science fiction manga they used to have in the 1980s and 90s, like Akira, Appleseed, or Ghost in the Shell...?” then Eden is your answer.

Maybe you’re a little suspicious when I make a claim like that; after all, those titles I just compared Eden to don’t need any cheerleading, like I’m doing here. Years before the "manga boom," those manga's creators, Katsuhiro Otomo and Shirow Masamune, earned their rep not only among manga readers but also with crossover US comics fans as well. Before Dark Horse published Akira in its original black and white, a colorized version was released through Marvel’s Epic line, whereas Dark Horse’s version of Ghost in the Shell was the first manga ever to make the cover of what was once the tastemaker in the U.S. comics market, Wizard magazine. Like Wizard, the manga boom too is gone—though I have a hard stare for anyone who takes that to mean it's time to step back from manga. Look at it this way: in 2014 there's as many different comic books on the U.S. market as ever, yet I seem to recall the last time there was a “comics boom" around here, Bill Clinton was president.

So if Eden deserves comparison to those classics, how come you’ve never heard of it? Media exposure might be part of it; unlike Shirow or Otomo's work, there are no anime or live-action adaptations of Eden. Format might also play a role. Otomo and Shirow’s works were drawn in the right-to-left reading order common in Japan, but in the US they were published “flopped,” so that they could be read left to right. There’s no doubt this helps to reach crossover US comics fans. But Eden, by the creator’s request, is published right-to-left format—which perhaps puts a barrier between it and those US comics fans that are open to manga when it comes to story or art, but are uncomfortable reading it Japanese style. Moreover, unlike Otomo or Shirow’s works, Eden is a shrink-wrapped title that comes with a “mature readers” label, something that often restricts the number of copies that stores order.

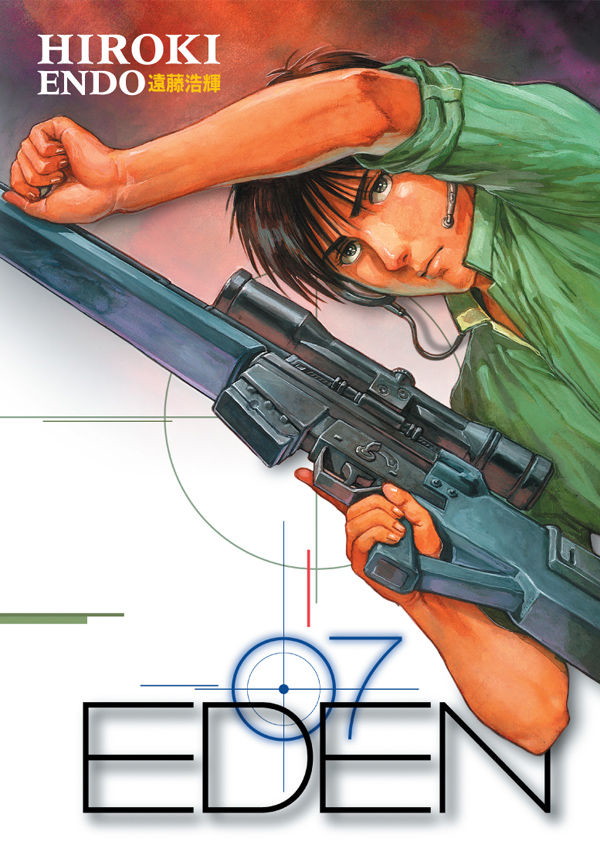

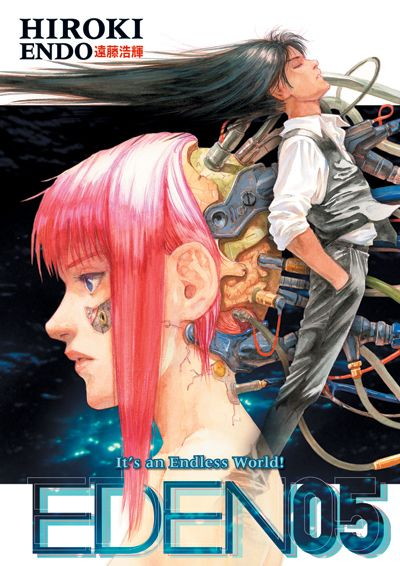

[please insert image Eden05.jpg here]

I haven’t yet said much about Eden itself, have I? When I say it’s like the works of Otomo and Shirow, I definitely don’t mean that Hiroki Endo is simply imitating their art style or narrative. Despite Eden’s unashamed elements of classic cyberpunk (if you’ve been missing stories with jacked-in runners talking of ICE, or thugs with slit visors and fingers full of monofilament wire, Eden fills the void), it’s not a retro tribute to manga of the eighties and nineties. Eden is a contemporary SF expression.

Like those earlier titles, Eden is a sprawling, cosmopolitan, postapocalyptic story of action, politics, and intrigue set on a future Earth—much of Eden takes place in urban South America—where a gruesome autoimmune disease called the Closure Virus has killed roughly 15 percent of the population; rather than rotting away to skeletons, the dead end up cracked shells of ossified skin through which the internal organs leak out. Though some cities are abandoned, Eden isn't one of those postapocalyptic stories where only a few survivors remain; Endo instead has imagined a pandemic that disrupts societies to the point of radicalism, yet leaves behind enough of the old world that we still recognize this future as a traumatized descendant of our own. The Closure Virus struck a generation before the “now” of Eden—now, the virus has returned, in a dramatically altered form that may prove the final reckoning for the human species.

Eden takes place in the early years of the next century, but, again like the works of Otomo and Shirow, its politics seems to comment on current issues. The future we see in Eden resembles theorist Thomas P. M. Barnett’s division of the modern world into two zones: the so-called “functioning core"—connected by economic globalization and backed by military power—and the “nonintegrating gap” where the core fights all its wars. The hero of Eden, Elijah Ballard (named, as you might guess, for the Biblical prophet and the British science fiction writer), is a teenager whose parents were raised during the plague in the "Eden" of the title: a reserve in the US Virgin Islands isolated from the chaos. Born with antibodies against the Closure Virus, the man and women left Eden, to know good and evil—particularly evil, as Elijah’s dad, Ennoia, becomes a South American drug lord at one end of the “gap." Ennoia deals clear-eyed in a business built on fear, cruelty, and degradation, but is aware nevertheless that his power is one of the few remaining counterforces against a global system of ostensibly greater ideals, but equal ruthlessness.

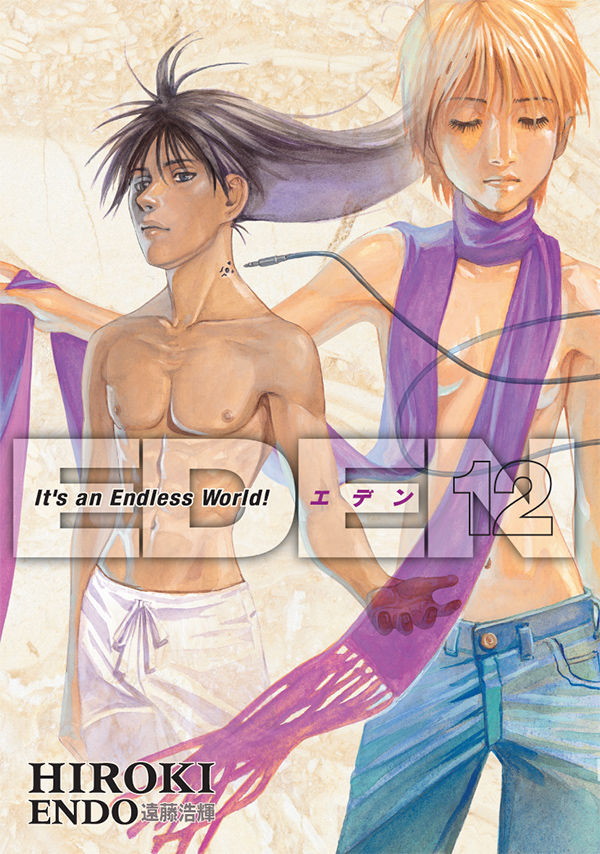

[please insert image Eden12.jpg here]

Leaving behind a rich kid's childhood of equal parts notoriety and privilege, his son Elijah starts to mature as he searches for his missing mother and sister. In Eden, this means the former private-school boy gradually becomes a dangerous young man as he enters a world of gangsters, mercenaries, prostitutes, cops, spies, scientists, terrorists, hackers, and activists. In Eden, the distinction between all these labels is often unclear, because Endo writes these characters as human beings who have their own ideas about their lives and what they mean.

Science fiction sometimes gets accused of being more interested in technology than human nature. I agree with Marshall McLuhan that technology is properly understood as an extension of human nature, made by humans for human purposes. And if we don't always understand the systems we create, that doesn't make them nonhuman; why should we expect to understand our systems better than we understand ourselves? But, like William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, Hiroki Endo certainly doesn’t believe that advancing science will necessarily unweave the twists put into us by our families, societies, and nations. No technology simply removes these things; just look at any online comment thread to see how unified instant global communications has made us.

Of course, if we were obliged to encounter all those others we resent face to face, we might find ourselves more understanding of them—or we might find ourselves fighting them to the death—or, quite possibly, both. That's exactly the kind of journey Elijah makes in Eden, our best manga you haven't read yet.

—Carl Horn

Manga Editor

Hiroki Endo's Eden may be our best manga you haven't read...yet.

Maybe you’re a little suspicious when I make a claim like that; after all, those titles I just compared Eden to don’t need any cheerleading, like I’m doing here. Years before the "manga boom," those manga's creators, Katsuhiro Otomo and Shirow Masamune, earned their rep not only among manga readers but also with crossover US comics fans as well. Before Dark Horse published Akira in its original black and white, a colorized version was released through Marvel’s Epic line, whereas Dark Horse’s version of Ghost in the Shell was the first manga ever to make the cover of what was once the tastemaker in the U.S. comics market, Wizard magazine. Like Wizard, the manga boom too is gone—though I have a hard stare for anyone who takes that to mean it's time to step back from manga. Look at it this way: in 2014 there's as many different comic books on the U.S. market as ever, yet I seem to recall the last time there was a “comics boom" around here, Bill Clinton was president.

So if Eden deserves comparison to those classics, how come you’ve never heard of it? Media exposure might be part of it; unlike Shirow or Otomo's work, there are no anime or live-action adaptations of Eden. Format might also play a role. Otomo and Shirow’s works were drawn in the right-to-left reading order common in Japan, but in the US they were published “flopped,” so that they could be read left to right. There’s no doubt this helps to reach crossover US comics fans. But Eden, by the creator’s request, is published right-to-left format—which perhaps puts a barrier between it and those US comics fans that are open to manga when it comes to story or art, but are uncomfortable reading it Japanese style. Moreover, unlike Otomo or Shirow’s works, Eden is a shrink-wrapped title that comes with a “mature readers” label, something that often restricts the number of copies that stores order.

I haven’t yet said much about Eden itself, have I? When I say it’s like the works of Otomo and Shirow, I definitely don’t mean that Hiroki Endo is simply imitating their art style or narrative. Despite Eden’s unashamed elements of classic cyberpunk (if you’ve been missing stories with jacked-in runners talking of ICE, or thugs with slit visors and fingers full of monofilament wire, Eden fills the void), it’s not a retro tribute to manga of the eighties and nineties. Eden is a contemporary SF expression.

Like those earlier titles, Eden is a sprawling, cosmopolitan, postapocalyptic story of action, politics, and intrigue set on a future Earth—much of Eden takes place in urban South America—where a gruesome autoimmune disease called the Closure Virus has killed roughly 15 percent of the population; rather than rotting away to skeletons, the dead end up cracked shells of ossified skin through which the internal organs leak out. Though some cities are abandoned, Eden isn't one of those postapocalyptic stories where only a few survivors remain; Endo instead has imagined a pandemic that disrupts societies to the point of radicalism, yet leaves behind enough of the old world that we still recognize this future as a traumatized descendant of our own. The Closure Virus struck a generation before the “now” of Eden—now, the virus has returned, in a dramatically altered form that may prove the final reckoning for the human species.

Eden takes place in the early years of the next century, but, again like the works of Otomo and Shirow, its politics seems to comment on current issues. The future we see in Eden resembles theorist Thomas P. M. Barnett’s division of the modern world into two zones: the so-called “functioning core"—connected by economic globalization and backed by military power—and the “nonintegrating gap” where the core fights all its wars. The hero of Eden, Elijah Ballard (named, as you might guess, for the Biblical prophet and the British science fiction writer), is a teenager whose parents were raised during the plague in the "Eden" of the title: a reserve in the US Virgin Islands isolated from the chaos. Born with antibodies against the Closure Virus, the man and women left Eden, to know good and evil—particularly evil, as Elijah’s dad, Ennoia, becomes a South American drug lord at one end of the “gap." Ennoia deals clear-eyed in a business built on fear, cruelty, and degradation, but is aware nevertheless that his power is one of the few remaining counterforces against a global system of ostensibly greater ideals, but equal ruthlessness.

Leaving behind a rich kid's childhood of equal parts notoriety and privilege, his son Elijah starts to mature as he searches for his missing mother and sister. In Eden, this means the former private-school boy gradually becomes a dangerous young man as he enters a world of gangsters, mercenaries, prostitutes, cops, spies, scientists, terrorists, hackers, and activists. In Eden, the distinction between all these labels is often unclear, because Endo writes these characters as human beings who have their own ideas about their lives and what they mean.

Science fiction sometimes gets accused of being more interested in technology than human nature. I agree with Marshall McLuhan that technology is properly understood as an extension of human nature, made by humans for human purposes. And if we don't always understand the systems we create, that doesn't make them nonhuman; why should we expect to understand our systems better than we understand ourselves? But, like William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, Hiroki Endo certainly doesn’t believe that advancing science will necessarily unweave the twists put into us by our families, societies, and nations. No technology simply removes these things; just look at any online comment thread to see how unified instant global communications has made us.

Of course, if we were obliged to encounter all those others we resent face to face, we might find ourselves more understanding of them—or we might find ourselves fighting them to the death—or, quite possibly, both. That's exactly the kind of journey Elijah makes in Eden, our best manga you haven't read yet.

—Carl Horn

Manga Editor