It’s funny that we speak not just of superhero worlds but of entire superhero “universes,” when most of the time they’re daytime soaps with superpowers. A soap opera is a kind of fictional setting defined by the presence of its cast of characters. There is no real background; take those characters away, and your world is gone, too. That’s one mode of storytelling, to be sure, and legitimate in its own way; as human beings we’re drawn to glamor and power, we’d like to think of ourselves as heroes (or at least, as cool villains), and sometimes we indeed act as if the world revolves around us.

But there’s another kind of fiction that involves a creator’s attempt to build up a world that seems like it existed before its main characters, and will go on existing after them. In fantasy fiction, the most famous example of this may be Tolkien’s Middle-Earth. In historical fiction, Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima first met this test in their most famous manga, Lone Wolf and Cub. The manga is based on a time and place that actually existed, but as creators, Koike and Kojima put in tremendous work to research it, and then equally hard effort to express it.

Itto Ogami is a badass equal to any superhero, a legendary figure of will, skill, and honor. Yet he’s one mortal man just like everyone else (and like you, the reader), and his saga is never just about him. Koike and Kojima knew that the reality of the world (and thus also the reality of a fictional world) is made by the existence not of the “main characters,” but the existence of everyone else—not only the people we know, but those people we’ll meet only once, and of those people we’ll never know at all; who never got to be “characters” in “our” story. Even the name of the manga suggests a fictional world can’t feel truly real if it must end with its hero: Lone Wolf and Cub. Real heroes die at last, and they don't return. They live on only as ordinary people do; in the memory and example of their lives, and in their children.

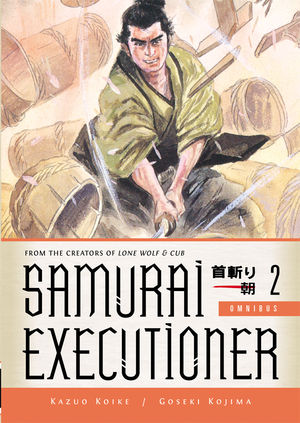

You can see how that world they built endures in two of the manga we’re publishing now. One, of course, is New Lone Wolf and Cub, the story of Itto Ogami’s son Daigoro once the bonds of parent and child between them are severed, as eventually they must be. Another is the Samurai Executioner Omnibus, vol. 2 of which is out this week. Samurai Executioner is that same detailed human world of Lone Wolf and Cub, but seen through the eyes of Yamada “Decapitator” Asaemon, a character who had only a walk-on part in Ogami’s tale. Proving their strength at world-building, Koike and Kojima turn their camera far around until Asaemon, not Ogami, is the main character, and we find a rich but different fascination in his own story.

Samurai Executioner is currently being published by Dark Horse in omnibus format, just as Lone Wolf and Cub is. That means not only more story for less money, but also larger pages. With Kojima’s artwork at a bigger size, I feel I’m seeing these stories in a new way, and one thing I particularly notice is his command of portraiture. It’s not just that “Decapitator” Asaemon has a different face than Itto Ogami’s; he also has different facial expressions than him, ones Ogami would never make. It’s remarkable because they’re both composed, disciplined characters; the differences are more effective precisely because they’re subtle; the look of the eyes, the set of the mouth. It’s a world not only of different people, but different heroes.

Lone Wolf and Cub is the saga of a wandering warrior, a man of tactics and terrain. “Decapitator” Asaemon carries a deadly sword like Ogami’s, but his stories are urban, for he is the executioner who beheads common criminals under the shogun’s rule, just as Itto Ogami once decapitated lords and nobles. Samurai Executioner is a police drama of Edo (Tokyo, as it was known in centuries past), and, just as the stories in Lone Wolf and Cub were as much about the reasons behind a kill as the assassinations Ogami carried out, the stories in Samurai Executioner are as much about the crimes and criminals as the justice meted out—justice which is not always just, as Asaemon is a man well aware that he serves a system that rules over a society. Koike’s observations about crime and law are often relevant for today—another demonstration of the world that lives on beyond its characters.

—Carl Horn

Manga Editor

It’s funny that we speak not just of superhero worlds but of entire superhero “universes,” when most of the time they’re daytime soaps with superpowers. A soap opera is a kind of fictional setting defined by the presence of its cast of characters. There is no real background; take those characters away, and your world is gone, too. That’s one mode of storytelling, to be sure, and legitimate in its own way; as human beings we’re drawn to glamor and power, we’d like to think of ourselves as heroes (or at least, as cool villains), and sometimes we indeed act as if the world revolves around us.

It’s funny that we speak not just of superhero worlds but of entire superhero “universes,” when most of the time they’re daytime soaps with superpowers. A soap opera is a kind of fictional setting defined by the presence of its cast of characters. There is no real background; take those characters away, and your world is gone, too. That’s one mode of storytelling, to be sure, and legitimate in its own way; as human beings we’re drawn to glamor and power, we’d like to think of ourselves as heroes (or at least, as cool villains), and sometimes we indeed act as if the world revolves around us.

But there’s another kind of fiction that involves a creator’s attempt to build up a world that seems like it existed before its main characters, and will go on existing after them. In fantasy fiction, the most famous example of this may be Tolkien’s Middle-Earth. In historical fiction, Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima first met this test in their most famous manga, Lone Wolf and Cub. The manga is based on a time and place that actually existed, but as creators, Koike and Kojima put in tremendous work to research it, and then equally hard effort to express it.

Itto Ogami is a badass equal to any superhero, a legendary figure of will, skill, and honor. Yet he’s one mortal man just like everyone else (and like you, the reader), and his saga is never just about him. Koike and Kojima knew that the reality of the world (and thus also the reality of a fictional world) is made by the existence not of the “main characters,” but the existence of everyone else—not only the people we know, but those people we’ll meet only once, and of those people we’ll never know at all; who never got to be “characters” in “our” story. Even the name of the manga suggests a fictional world can’t feel truly real if it must end with its hero: Lone Wolf and Cub. Real heroes die at last, and they don't return. They live on only as ordinary people do; in the memory and example of their lives, and in their children.

You can see how that world they built endures in two of the manga we’re publishing now. One, of course, is New Lone Wolf and Cub, the story of Itto Ogami’s son Daigoro once the bonds of parent and child between them are severed, as eventually they must be. Another is the Samurai Executioner Omnibus, vol. 2 of which is out this week. Samurai Executioner is that same detailed human world of Lone Wolf and Cub, but seen through the eyes of Yamada “Decapitator” Asaemon, a character who had only a walk-on part in Ogami’s tale. Proving their strength at world-building, Koike and Kojima turn their camera far around until Asaemon, not Ogami, is the main character, and we find a rich but different fascination in his own story.

Samurai Executioner is currently being published by Dark Horse in omnibus format, just as Lone Wolf and Cub is. That means not only more story for less money, but also larger pages. With Kojima’s artwork at a bigger size, I feel I’m seeing these stories in a new way, and one thing I particularly notice is his command of portraiture. It’s not just that “Decapitator” Asaemon has a different face than Itto Ogami’s; he also has different facial expressions than him, ones Ogami would never make. It’s remarkable because they’re both composed, disciplined characters; the differences are more effective precisely because they’re subtle; the look of the eyes, the set of the mouth. It’s a world not only of different people, but different heroes.

Lone Wolf and Cub is the saga of a wandering warrior, a man of tactics and terrain. “Decapitator” Asaemon carries a deadly sword like Ogami’s, but his stories are urban, for he is the executioner who beheads common criminals under the shogun’s rule, just as Itto Ogami once decapitated lords and nobles. Samurai Executioner is a police drama of Edo (Tokyo, as it was known in centuries past), and, just as the stories in Lone Wolf and Cub were as much about the reasons behind a kill as the assassinations Ogami carried out, the stories in Samurai Executioner are as much about the crimes and criminals as the justice meted out—justice which is not always just, as Asaemon is a man well aware that he serves a system that rules over a society. Koike’s observations about crime and law are often relevant for today—another demonstration of the world that lives on beyond its characters.

—Carl Horn

Manga Editor