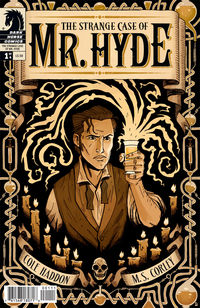

An Introspective look at Horror by Cole Haddon

“More blood,” I typed. “Garish, bright red blood.” This was an e-mail to Jim Campbell, the colorist who helped artist M. S. Corley and me bring my first comic book, The Strange Case of Mr. Hyde, to life. “Check out these stills,” I told him, attaching images from Hammer Films’ The Curse of Frankenstein to the e-mail. “I want our book to look like that.”

The Strange Case of Mr. Hyde began as a homage to Hammer horror, in fact, but quickly grew into a love song to the whole of the gothic horror I loved when I was young—from silent horror movies, to Universal’s monster movies and producer Val Lewton’s horror oeuvre, to directors Tod Browning and John Brahm, to Mario Bava’s terrifying and often twisted works. I read fanatically as a kid, novels and comic books of all kind, but I watched even more movies and today—I’m thirty-four now—I don’t think I’ve ever come close to escaping that celluloid obsession. It’s only gotten worse. I know once I discovered Dario Argento, Sergio Leone, Sergio Corbucci, and Asian martial-arts cinema, my love of cinematic blood—its ability to actually make violence less and, at the same time, more horrific—only intensified. This is ironic, I should point out, as in real life I can’t stand the sight of the stuff.

Strange Case was thus to be a bloody affair, from the start. How could it not be, what with Victorian London’s two greatest villains, Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde and Jack the Ripper, taking each other on? But it would also be something else, I realized as I developed the idea further. Strange Case would become my opportunity to ask a simple question of my hero, Inspector Thomas Adye of Scotland Yard: why do you believe what you do? It’s a question I’ve long been fascinated by and one I think most people fail to ask themselves. Where did you get your ideals? How did you come upon your ethics? Who proscribed the morality you now expect in others? If most people were honest, they’d have to admit that what they believe is not the product of study, rational reasoning, or deep introspection. It isn’t the product of asking questions in any way most of the time either. If anything, it’s the product of the complete opposite. I’m not saying I’m above this; and I’m definitely not interested in being controversial. I’m simply curious about the question itself: why do you and I believe what we do? That’s what Dr. Jekyll became for me: a mouthpiece for that question, demanding an answer from Adye. His serum, which had essentially released Mr. Hyde (his id) five years earlier in the original Robert Louis Stevenson novel, showed him how full of it the world around us is. Jekyll now preaches liberation from such slavish thinking. He preaches a disturbing truth that Adye, the most puritanical stick in the mud you can imagine, is not at all prepared for.

Also, there are a lot of big fights, sex, and shit blowing up.

Because, after all, these things—and blood, of course—are just kind of cool.

It’s been a wild ride for the past two years, developing this comic book, selling it as a movie to Skydance Entertainment, and then writing the screenplay adaptation myself. The release of The Strange Case of Mr. Hyde isn’t the end of the road, I hope. There’s the movie to look forward to now, and then, if you love Adye and Jekyll’s world—and garish, bright red blood, of course—sequels to the comic book. You’ll find more than a few Easter eggs in this first book’s pages, alluding to what’s still to come. I hope you enjoy finding them, I hope you enjoy the book itself enough to ask for more, and, most of all, I hope you find yourself wanting to check out some of the movies that changed my life and inspired the comic book itself. But don’t do it because I told you to. Make up your own mind.

Ten movies to add to your Netflix queue:

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957; dir. Terence Fisher)

The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933; dir. Michael Curtiz)

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931; dir. Rouben Mamoulian)

The Undying Monster (1942; dir. John Brahm)

Captain Clegg, AKA Night Creatures (1962; dir. Peter Graham Scott)

The Body Snatcher (1945; dir. Robert Wise)

The Invisible Man (1933; dir. James Whale)

The Brides of Dracula (1960; dir. Terence Fisher)

Hangover Square (1945; dir. John Brahm)

Black Sunday, AKA The Mask of Satan (1960; dir. Mario Bava)