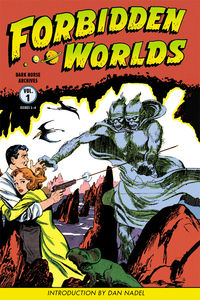

Forbidden Worlds, like much of what American Comics Group (ACG) released, is an understated title that has quiet gems sprinkled throughout its run. This title was the follow-up to Adventures into the Unknown, which began in 1948 and was the first ongoing horror title in comics, beating EC by nearly two years. With sales booming and, indeed, EC nipping at its heels, ACG launched Forbidden Worlds in 1951. Skewing towards the supernatural over the straight up horrific, ACG was a relatively clean house, so gore and excessive nastiness was out—instead there were well-executed short tales of the fantastic employing the usual tropes of vampires, apocalypses, spooky towns and strange creatures.

Forbidden Worlds, like much of what American Comics Group (ACG) released, is an understated title that has quiet gems sprinkled throughout its run. This title was the follow-up to Adventures into the Unknown, which began in 1948 and was the first ongoing horror title in comics, beating EC by nearly two years. With sales booming and, indeed, EC nipping at its heels, ACG launched Forbidden Worlds in 1951. Skewing towards the supernatural over the straight up horrific, ACG was a relatively clean house, so gore and excessive nastiness was out—instead there were well-executed short tales of the fantastic employing the usual tropes of vampires, apocalypses, spooky towns and strange creatures.

Partly this was owing to ACG’s perennial light touch, thanks to editor Richard Hughes, who introduced the new series as the answer to readers’ requests: “So here it is—your own special magazine—chock-full of the very thrilling fare we’ve learned you want! We dare you to read each and every issue of this startling new publication—to venture into forbidden, Unknown worlds!” This is followed by a solicitation for more letters—all very jovial and yet quite serious. Hughes did indeed respond to and discuss readers’ letters over the years, which helped build ACG a devoted, if small, audience.

It takes a certain sense of the absurd to launch a new comic book with a lead story called “Demon of Destruction.” But then, Hughes had Al Williamson and Frank Frazetta working on it, so maybe it wasn’t too much of a risk. This is Williamson’s first of a handful of appearances in Forbidden Worlds—inked by Frazetta. Williamson was just twenty years old at the time and Frazetta only twenty-three, both breaking into the business simultaneously and on the cusp of work for EC that would make them both famous in fandom circles. “Demon of Destruction” shows both artists at their best. Williamson, obviously enthralled with Alex Raymond (whose Flash Gordon and Rip Kirby strips he would later draw) penciled the piece as a classic hero-and-dame adventure, complete with swirling lines for atmosphere and stoic poses for nobility. Frazetta brought his vibrant rendering skills to the titular demon, whose scale and strength is evident in Frazetta’s swooping, dynamic marks as cities and landmarks are crushed. Everything here is high drama and the tale even ends with a passionate embrace, heads posed just so and rendered with fleshy passion—playing to all of Frazetta’s strengths. Williamson’s other contribution to this volume, “Skull of the Sorcerer,” brings in another special guest: Wally Wood. The young cartoonist’s lines are all over this story, accentuating the knotty patterns of the trees, and adding shadows and worry lines to the stressed faces of our hero. After Frazetta’s graceful, easygoing flow, coming upon Wood’s more neurotic work is bracing.

The proceedings were all guided by Richard Hughes, about whom we know very little, but what we do know has been unearthed by Michael Vance and published first in his book, Forbidden Adventures, and then in Alter Ego #113 and #114. Hughes was born Leo Rosenbaum and lived from 1909 to 1974. According to Vance, “at ACG’s peak, in 1952, Hughes edited and wrote for at least sixteen titles.” He’d arrived at ACG in 1943 and stayed until it closed around him in 1967—a particularly long and extremely strong run for any editor. He was at his best writing romance comics and, later, Herbie, which utilized his hip sense of humor and love of wordplay.

Hughes helped make ACG known as a particularly artist-friendly house and attracted a number of unique talents who stuck around, apparently, for the quality of Hughes’s treatment and his scripts. In an interview for Vance’s Forbidden Adventures Williamson remembered Hughes: “He was a very sweet man. I think he was a very honest man. The editor that I think I like best—this is not putting down EC guys at all—the one that I think I feel I should have done more work for, should have been the better artist for, is Richard Hughes.” And while the artists of these stories have mostly been identified, the writers remain unknown—the records are mostly empty. It’s possible that some were written by Hughes’ assistant editor, Norman Fruman, or by any number of freelancers passing through the office.

The issues in this volume are also graced with art by Emil Gershwin (“The Way of the Werewolf” and “Lair of the Vampire”), a distant relative of George and Ira’s and a stunningly talented unknown artist. His thick, expressive brush strokes bring to mind Harvey Kurtzman’s drawings for EC, as well as work by Alex Toth, but the imagery is so assured that it begs to be taken on its own terms. George Wilhelms (“The Fiend in Fur” and “The Doom of the Moonlings”) is another pleasant surprise in these pages. A journeyman artist who had a lush and pulpy style somewhere between Virgil Finlay and Matt Fox, Wilhelms’ labored-over imagery was all too rare in comic books at the time. He worked in comics from the 1940s through the 60s, and appears to have peaked with his work for ACG.

Finally, as is the case with ACG in general, there is Ogden Whitney. One of the last mysteries in comics, Whitney began in his comic book career in 1939, joined ACG in 1950, and stayed until the bitter end. Little is known about the man himself aside from a stint in World War II and rumors of a drinking problem. Norman Fruman remarked that “Whitney was very correct. He seems to me to have been kind of withdrawn. Not a socially amiable, but not unamiable, person. Someone who might be coming in like an accountant.” Whoever he was, Whitney meshed perfectly with Hughes’ sensibility and became the emblematic visual force behind the company—the man responsible for giving the romance and fantasy comics an unnervingly bland look, as well as, of course, the co-creator of Herbie. Whitney has just one story here, “The Vengeful Spirit”, and it finds him still entrenched in a “good girl” mode of art, with beautiful women front and center and hapless men all around.

In these four issues, Forbidden Worlds gets off to a strong start and also indicates the direction of ACG itself. These are strong stories that, unlike those of EC, are not highly eccentric, but nonetheless feature solid and, at times, stunning storytelling marked by the high standard of craft that Richard Hughes cultivated throughout his run.

Dan Nadel

June 2012

Special thanks to Michael Vance, Roy Thomas, and Jim Vabedoncoeur.

Dan Nadel is the owner of PictureBox, Inc. (pictureboxinc.com), a Grammy Award-winning publishing company. Dan has authored books including Art Out of Time: Unknown Comic Visionaries, 1900–1969, Gary Panter, Art in Time: Unknown Comic Book Adventures, 1940-1980, and, most recently, co-authored Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art. He is the coeditor of The Comics Journal, and has published essays and criticism in The Washington Post, Frieze, and Bookforum. As a curator, he has mounted exhibitions including: “Return of the Repressed: Destroy All Monsters 1973-1977” in Los Angeles; "Karl Wirsum: Drawings 1967-1970" in New York; the first major Jack Kirby retrospective, "The House that Jack Built” in Lucerne, Switzerland; and “Macronauts” for the Athens 2007 Biennale in Greece. Dan lives in Brooklyn.