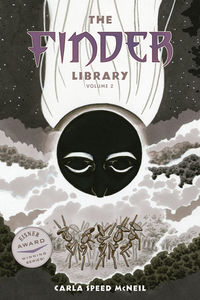

I feel like I’ve written this a dozen times or more over the last several years. Ifeel like I’ve spent a lot of the last decade trying to get people to pay attention to Carla Speed McNeil and Finder. Which has meant, at least in part, years of trying to drag Speed out into the light and make her wave her arms a bit so people could see her. Which she’s not very good at. So I feel kind of vindicated that here Finder is again, in a nice new edition paid for by other people. The thing is that, given the above, you may not be completely sure what you’re holding right now. So here I am again, waving my arms on behalf of Finder. I may never get tired of it.

I feel like I’ve written this a dozen times or more over the last several years. Ifeel like I’ve spent a lot of the last decade trying to get people to pay attention to Carla Speed McNeil and Finder. Which has meant, at least in part, years of trying to drag Speed out into the light and make her wave her arms a bit so people could see her. Which she’s not very good at. So I feel kind of vindicated that here Finder is again, in a nice new edition paid for by other people. The thing is that, given the above, you may not be completely sure what you’re holding right now. So here I am again, waving my arms on behalf of Finder. I may never get tired of it.

Speed has described Finder—when pinned to the wall for a way to describe it at all—as “aboriginal sf.” When she thinks I’m not looking, she will also call it “fantasy.” And, honestly, speculative fiction has gotten so fuzzy around the edges in the last forty years that it’s sometimes gotten absurdly hard to differentiate some of it from fantasy or any other goddamn thing. Science fiction is one of those things that’s, on closer examination of the genre, actually kind of slippery to define. You can look for the novum, the new thing—Finder certainly has those. But I can name you a bunch of other books that are inarguably considered science fiction that don’t have them. Fantasy tends not to have the novum, that thing that is speculative—except, of course, when it does.

I’ve found few working definitions that seem to really encompass the form. But let me try this one on you, from the sf writer Frederik Pohl: “Science fiction is a way of thinking about things.”

Finder is a way of thinking about things.

Finder takes an aborigine, a native from a place where there is still contact with sand and soil and the wind and the world, and places him in a series of future urban societies. Not as an avatar of the arch, doomed John the Savage from Huxley’s Brave New World, nor as some noble primitive, nor even as some naive plainsman lost in the big cities. The complex, charming, slightly callous Jaeger comes from a society just as ordered and ruthless as the ones he now walks through. And because of that there is a sense that the earthy Jaeger, in his travels, is in fact experiencing versions of what his tribal society may grow into. That Finder is speculation on the themes of tribe and family. A way of thinking about where we, barely out of the woods ourselves, are going. Jaeger, the Finder—a hunter/tracker—can move from, if you like, the court to the country, as he wishes and as circumstances dictate. The people he interacts with in the cities, by and large, cannot. Escape from the modern world, and its impossibility, is a constant theme. Jaeger can go where he likes, but he cannot escape himself—his role as a tribal sin-eater, and the other destructive compulsions I won’t mention here. He finds people, and he will be a scapegoat for them. But he’s almost entirely lost himself, and the people he meets don’t want to be found.

But the tone, for all that, isn’t a note of black depression. There is joy in this work, and people who find ways to live. And there is shagging. There is an awful lot of shagging.

The real joys of the work, I leave you to discover for yourself. Carla’s deft, warm, clever dialogue, and the gorgeous and intelligent art. Her capability as a cartoonist sneaks up on you: so organic and easy does her line appear that it can take a while to realize what she’s really doing with body language, the way people wear clothes, operate their environment, the sheer complexity of facial expressions that she seems to capture so effortlessly. There’s hard thought behind every single panel, a devotion to the full spectrum of storytelling that is rare and lovely.

These books are among my treasured favorites of the last ten years. I hope you love this one as much as I do.

—Warren Ellis

A hotel room in Berlin

February 2011