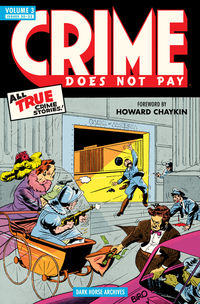

We at Dark Horse Comics celebrate the history of comics and like to share that history with our fans. Since last year, we have been sharing the old Crime Does Not Pay series that almost defines the Pre-Code Authority era of comics. Such bizarre tales in these collections. And we have some very special people who understand the history of comics all to well. We'll be bringing you these Introductions to our Archive editions to show you where this industry came from. Enjoy.

Now bear with me, ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls . . . There’s going to be a bit of rambling here, but I’ll get to a point or two, sooner or later.

Now bear with me, ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls . . . There’s going to be a bit of rambling here, but I’ll get to a point or two, sooner or later.

In the April/May 1992 issue of Film Comment magazine, the actor James Woods wrote a piece entitled “Guilty Pleasures,” in which he ran through a list of movies that he knew weren’t very good, but which he was very fond of. It was this piece that freed me up to be comfortable with some of my own questionable choices in film, television, music, and popular culture in general.

I’d been struggling to find the language to convey the fact that I know, intellectually at least, that just because I like something, that affection doesn’t grant the material in question any kind of imprimatur of quality. It can still be lousy—and I’ll still like it.

For me, this is mostly about music. Sheb Wooley, Spike Jones, Ray Stevens . . . I could go on, but you get the picture—or you will if you’re under fifty and use, as John McCain would have it, the Google.

Now when I was a kid, in the early sixties, I was a golden age comic book collector. We didn’t call them that—they were just old comics. They were (reasonably) affordable, selling from about two dollars and fifty cents a pop for midwar stuff, to as high as twenty-five bucks for special issues—the specialness defined by want.

It was mostly DC comics that I collected, vintage versions of the stuff that Weisinger and Schiff were turning out at DC back then. In the course of this, I made a number of discoveries—and one was that, from a visual perspective, the most beautiful work being done back then was at Quality Comics.

Those books were drawn by serious talent—the likes of Lou Fine, Reed Crandall, Jack Cole, and Will Eisner. All four of these guys were born before 1920, and thus had a bit more craft under their belts than most of the guys with whom they were competing.

The other discovery was that DC’s books were mostly the work of then-teenaged kids, the likes of Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane, Joe Kubert, and Alex Toth—all of whom were the only artists working in what would come to be known as the silver age of comics that I and my little crew of nascent comics geeks held in any regard.

Their work back then was understandably crude—they were ninth and tenth graders, for God’s sake—but they were inventing a language that would be codified by the end of the decade, setting the tone for the history of comics—at least until the second coming of Jack Kirby, once again partnered with a taller and better-looking Jew, would introduce fractious snarkiness to comics in The Fantastic Four, changing everything.

Which brings us (finally, some of you are saying) to the material at hand. When Philip asked me to write the introduction to this book, I jumped at the chance. I’m much more familiar with the Crime Does Not Pay stuff from the fifties, so I had no idea what to expect.

To put it kindly, this stuff is far from the most beautifully executed material produced at Quality, or even the crude but vital stuff coming from those underpaid kids at DC Comics. The Crime material you hold in your hands is crude at best, sloppy at worst—but even in those instances, there’s a visceral quality of adolescent hysteria that makes these stories page turners for the most part.

To call this work inconsistent is to grossly understate the meaning of the word. I’m guessing many of these stories were drawn by diverse hands—or, at the very least, the artists were all too frequently at the mercy of swipes, hitting highs and lows as the available and appropriate stuff from which to steal waxed and waned.

My first job in comics was as an assistant to Gil Kane. My work was awful, beneath criticism, so I was a gofer for him, learning everything I could by watching him work and listening to his (deeply opinionated, completely one-sided) history of comics and his take on the current state of the form.

Gil had worked as an assistant himself, as had Joe Kubert—and I’m sure they and the other guys who did the same learned a shitload from their mentors and ultimately moved on over the next few decades to transcend their influences.

The point I’m trying to make here is that the guys who did this work for Biro, Gleason, and Wood were assistants at best, who never really moved on from that level of craft—with the notable exception of Dick Briefer, best remembered for his wonderful version of Frankenstein. The rest of these cats are utterly unknown to me, both those who managed to sneak in a signature, and those whose work remains unsigned.

I’m guessing that most of them, if they pursued a career in what was called the applied arts back then, ended up working in studios or even evolving into illustrators. One of the tropes/dirty little secrets among illustrators born in the twenties is that if you scrape deep enough, you’ll likely find a comic book job or two . . . so who knows? One or more of these artists might have actually had a legitimate career in illustration. The mystery remains.

So at best, the work here feels very much like fanzines, drawn by children, for an audience of children. The writing is, for the most part, on a par with the artwork, visceral at best, weirdly repetitious at worst. I was actually hoping to see more blood and guts both in the drawing and the writing. So sue me. As a child of fifties New York, I grew up with the necroporn of the Daily News and the Daily Mirror—in a world that still looked a hell of a lot like Weegee’s photographs. To this day, I remain a sucker for sensationalism.

And yet . . . in a perfect illustration of reach exceeding grasp, there are, scattered throughout this volume, exceedingly interesting examples of attempts at narrative, stabs at graphic ideas not even close to being examined at the slicker houses . . . not the least of which is the frequent use of full-page splashes for the most violent money shots in a given issue—extremely unusual at this time in the then-short history of comics.

In 1942, Alfred Hitchcock made a picture entitled Saboteur. It’s a minor film in his body of work, but what’s interesting and important to me is that it acts as a sketch for North by Northwest, a far more successful and critically acclaimed movie that could not have existed without the earlier, lesser-known production.

That’s how I feel about much of this volume . . . that this material, crude as it may be in most cases, is a sketch, or a series of sketches, anticipating and prefiguring superior work to come.

All of which brings me around to my first paragraph and to the concept of guilty pleasures. Despite every critical observation above, in spite of all my caveats and concerns, I love this stuff—for its adolescent insanity, for its id-based nuttiness, for the very crudity that is its most defining quality—and I dearly hope you do the same.

Thanks again to Philip for asking me to write this introduction, and for your patience and kind attention.

Howard Chaykin—a prince.

Ventura, California

March 2012