Let’s be honest about this, here.

Let’s be honest about this, here.

Crime pays. Crime pays well. Crime pays very, very well, in fact, and it’s been doing so since shortly after Cain took the long walk out of Eden on his own.

At the very least, you now hold in your hands a collection that’s been printed up to make a profit. All aspirations to posterity and the grand history of our tortured and much-abused medium of Comics aside—and I’m more than willing to acknowledge and even honor the same—no publisher is publishing anything out of the goodness of their heart. Call me a cynic, but, seriously. Otherwise, you’d be buying this at cost.

So there’s that to consider.

We live in a world surrounded and framed by crime in its myriad forms. A news media that thrives on crime, leads with crime, retells and dissects and examines and glorifies all that is criminal, macabre, and depraved. We follow the justice system like ants who’ve found the picnic. We consume the offerings of an entertainment industry that does the same, that portrays serial killers as sympathetic protagonists, or that offers a steady forty-two-minute diet about those who pursue, capture, and bring to justice the offender. The longest-running American television franchise currently on air does not exist, nor does it continue to machine out episode upon episode of rape, murder, and similar abuse, if crime does not pay.

Insert gavel sound here.

Crime pays so well, in many cases, it’s managed to make itself legitimate, or nearly so. Look to politics. Look to Wall Street. Look at a financial crisis that has crippled the economy of a planet.

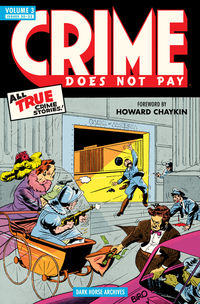

Now, let’s spin it back, shall we? To the lovingly reproduced publication you hold in your hands. In its heyday, nearly a million copies of Crime Does Not Pay were being sold a month. You think that’s chump change? All these exquisitely lurid and devilishly detailed covers, villainy depicted in glorious color. Bullets flying and flesh tearing and the whiff of sex to go with your violence, a porcelain-skinned beauty revealing the gentle swell of a blood-spattered breast. Tell me that wasn’t designed to grab you by the throat with one hand while your pocket was being picked of hard-earned cash with the other?

Of course it was. And you know it.

And you chump, you sucker, you played right into it, didn’t you? Just like I did; I’ll admit it. You glimpsed that dark alley as you went past, and you thought you saw something glint in the darkness, the muffled cry for help, and you wanted to take a closer look. You saw that ice-cold blond strut past, flanked by two hulking henchmen, and you wanted to know just how far she would go to keep them on leash, to get them to do everything she wanted.

You bought it. You bought into it.

You, my friend, are an accessory, and before you say another word, you may want to lawyer up.

Crime pays. Crime always has.

But crime, as these gorgeous reprints never cease to emphasize, has its own cost, as well.

*

There’s a terrific, energizing contradiction at work within these pages, an engine that makes the whole coalesce, and it’s nowhere better illustrated than in the narrative device of Crime himself, Crime personified, the ghostly figure who gleefully tells us of his triumphs, conquests, and students. Always students, always that word. Crime is the master, and the rest of us are just attendants at his knee. He’s here to teach, and in the first blush, we come to learn.

That’s the tension, right there. The titular lesson and its not-so-very-well-hidden corollary. Crime does not pay, because you end up dead, or in prison, or betrayed and bleeding out in a ditch somewhere. Crime does not pay, because when the accounting is done—and there is always, always, an accounting—the price is ultimate; the price is your life.

Yet over and over again, we’re witness to larger-than-life men (and occasionally women) who beat the system, at least for a time. They’re living large; they’re living the dream; they are, to be blunt, absolutely badass. Disagree? Take a look at “The True Life Story of Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano,” herein. It’s unattributed—my money is on either Dick Wood or Lev Gleason himself as the author—and never mind the “True Life Story” bit, but witness Luciano being “taken for a ride.”

“Luciano became a human pincushion as the gangsters plunged stilettos into his arms, face, and body . . .”

And he survives.

And he strikes back.

Or the story of Marty Durkin, in “The Dead-Eye Romeo,” where Burlockoff’s art renders the villain with Clark Gable features. Handsome, self-confident, daring, and a crack shot to boot. Women quite literally throwing themselves at him, his audacity such that the police are flummoxed. A man who lives a life of absolute independence and freedom.

And in the end? Durkin pays—of course he does, because he must—but you get the definite feeling that at the end of his road he settled that bill cheerfully. Yes, he paid.

But seeing him behind bars at the end of the story, you’re left wondering if he didn’t get his money’s worth.

*

There’s another subversive little gem of criminal accountancy within these pages, but you may miss it at first blush, because it is not, technically, a comic. It’s a prose piece, another by Dick Wood, “The Boy Detective and the Butchered Corpse.” Maybe seven hundred and fifty words, tops. Despite the title, it’s not even a mystery, really, as much as a reporting of events, presented as true to life. At first read, it’s wrapped in the same moral mantle that Crime himself wears—villainy is committed, and justice is ultimately served in the end. Because, after all, justice must be done. No matter the cost.

But the cost in this story seems damn high, to me, and while it’s more implicit than explicit, Wood himself certainly hints at it come the end. The cost is not solely a son losing his father, but his family, perhaps his community, as well. Our boy detective does right, but I can’t help but wonder what happened to him after, and what becomes of him as a result.

And I wonder that even knowing our boy detective, in all likelihood, never existed anywhere outside of Dick Wood’s imagination.

*

Remembering that it was comics like these that brought the almighty wrath of protecting the children down upon the industry, I am constantly struck by all that is not said within these stories. We are privy to extraordinary violence in these pages, with art that ranges from perfectly serviceable to far ahead of its time. Where the violence itself is not outright explicit, it is nonetheless remarkably evocative, thanks to the efforts of artists like Jack Alderman, Alan Mandel, Bob Wood, Charles Biro, and many others, some of whose names—sad to say—are lost to history.

The violence, as I said, is unflinching. In true American fashion.

And in true American fashion, the sex is flinching so much you’d think it was having a seizure. Some of the most cruel, most savage crimes recounted (or imagined) within these pages are crimes that are never truly acknowledged. “The Strange Saga of Rafael Red Lopez,” for instance, reads, in the final analysis, as a tale of revenge, and as a result rather conveniently—or perhaps by necessity—avoids dwelling on Fay Walters, the true innocent of the piece. Her brutal, repeated rape and ultimate murder occurs between panels, quite literally in the gutters, barely deserving of a passing mention. Similarly, the depravities of “Dimiran the Demon,” brought to exaggerated life by Bob Wood’s pencils, dripping with sadism, bondage, and sexual torture.

These are the crimes unspoken, and these are the same crimes that sent Wertham into a tizzy, no doubt. Bad enough the pages were soaked in booze and blood, but what was happening that we couldn't see? The mind runs rampant, and undoubtedly did.

And you know that didn’t hurt sales, either.

*

There’s one last story I want to mention here, an elegant little piece written by Wood and drawn by Jack Alderman. “Hex Horror,” set in 1929, is a tale of superstition, mob violence, and fearmongering in a Pennsylvania that shares more with Transylvania than America. We even get lit torches. It is, in every way, exactly the story you would expect.

Except the victim is a man named Nelson Rehmeyer, a name that, to a readership soaked in the brine of World War II, has a very distinct national association.

More than that is the fact that the true perpetrator of the crime goes unpunished, surely a rarity in the pages of Crime Does Not Pay. Old Madame Dell, who starts the ball of hatred rolling, vanishes from the narrative entirely, so that, at the end, it is only the mob who are made to pay for their crime. The person who instigated the chain of events, who threw—pardon the pun—gasoline on the flames? She’s nowhere to be found.

But most crucially of all, at least to me, is the motive behind the crime, or more precisely, the lack thereof. In all the tales prior, there’s always some perceived gain to be found in the crime: money, most often, or sex, even when unspoken. Power or prestige. The feeding of some dark and twisted deviant urge, perhaps.

Here, however, Old Madame Dell’s condemnation of Rehmeyer serves no discernible purpose; neither she, nor the members of the mob, benefit in any way from his murder. They gain nothing. Not money, not property, not power. Nothing.

They murder Rehmeyer because they are told he is the source of their problems. They murder Rehmeyer because they are led to believe he is different.

And maybe they murder Rehmeyer because they want to burn a man alive.

This isn’t a story about the cost of crime, or its price. This has become a story about something else entirely.

*

So where does that leave us? Today, now, holding these reprints, Crime eager to tutor and admonish us in the same breath. Wiser? More sophisticated? More cynical?

“Crime does not pay,” they said, and we nodded our heads and agreed with them, and all of us were thinking exactly what they were thinking when they said it.

Crime does not pay?

Tell me another.

—Greg Rucka

Portland, Oregon

January 2012