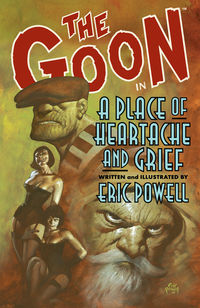

The Goon has returned to a monthly release at a Local Comic Shop near you and we can't be more stoked. The humor and action are about to amp up and we don't want you to miss any of it. Over the next few months we will be posting more of these intros from The Goon Trade Volumes and more entertaining items to keep this Eisner winning series at the forefront of your mind. If you're looking for a free issue of The Goon to get you started click here. Read the latest Goon issue here: The Goon #41

There’s a club-footed gorilla fighting a rabid zombie baby in a basement. There’s a hulking undead transvestite tearing up backyards, and the local landlords’ association hasn’t even got around to repairing the damage done in the last city-wrecking giant-monster rampage. The watering holes are crowded with cornpone, toothless rednecks, the sort of country gentlemen who think of Deliverance as highbrow romance. This is no place to raise kids. What are they going to do for fun, fight each other over fish guts? Yeah. Pretty much. I’d say the place is going to hell, but I hear property values are higher there.

There’s a club-footed gorilla fighting a rabid zombie baby in a basement. There’s a hulking undead transvestite tearing up backyards, and the local landlords’ association hasn’t even got around to repairing the damage done in the last city-wrecking giant-monster rampage. The watering holes are crowded with cornpone, toothless rednecks, the sort of country gentlemen who think of Deliverance as highbrow romance. This is no place to raise kids. What are they going to do for fun, fight each other over fish guts? Yeah. Pretty much. I’d say the place is going to hell, but I hear property values are higher there.

This particular bit of imaginary real estate is called Lonely Street and it belongs to a Tennessee native named Eric Powell. He’s been spiriting people off to the joint for ten years now, which is how long he’s been writing and drawing The Goon, a project which has, in due course, earned him a seat at the table with Kirby, Eisner, Chester Gould, Hal Foster, and Al Feldstein . . . the most talented and inventive artist-writers ever to apply their gifts to the comic-book/strip form.

You will note that most of those names belong to men who are dead, men who did their greatest work in the postwar years, back when people thought of dog racing as a sport and mentholated cigarettes as good for the lungs. Not a simpler time, as is often imagined, but one in which people maybe knew less and felt more. I do not think it is an accident that The Goon—the top-heavy stoic who rules the neighborhood with his cheerfully mouthy sidekick Franky—strides jaw-first through a murky 1950s noirville of the sort Eisner drew, Bogart stalked, and Mike Hammer wrote about. Lonely Street is, after all, not just a backroad of the mind, but one of history, reaching straight into our pop culture memories. Powell isn’t only a cartoonist: he’s a cartographer too; and The Goon is not just an entertainment, but a map, showing all the important geographic and cultural features of a country that isn’t real and yet exists none-the-less in the imaginations of all those who love and live for pulpy brawl-filled comic books, slobbering Lovecraftian horrors, the come-and-get-it poses of Bettie Page, and the rat-a-tat-tat rhythms of Cagney-era gangster films.

How did Powell discover the route to such fertile storytelling territory? I kind of think a writer or an artist never finds their way to a place like Lonely Street by consciously searching for it. It’s the sort of place a creator can usually only find by not looking for it. Powell probably first located Lonely Street while just screwing around, trying to doodle something that would make him and his degenerate friends laugh. He was out, in other words, for an imaginative joyride. And still is. Eric Powell, like Kirby, like Feldstein, isn’t interested in drawing for the ages, but in giving himself and his readers a rush right now. You paid for some entertainment and you’re going to get a face full. This is Powell’s religion and his business—as it was the faith and work of all those other aforementioned funnybook gods—and as a result, almost inevitably, The Goon is already timeless. As The Goon himself notes, at one point in the following pages: “Ain’t nothin’ as complicated as it seems.”

In the story you are about to read, The Goon and Franky get themselves a smokin’ new set of wheels (a ’49 Buick Roadmaster I believe). I can’t help looking at their sweet new ride as a kind of talisman, a warning of things to come, a sign that the adventures of The Goon are shifting into a brand new gear. It is hard not to feel that Powell is accelerating us toward the heart of his grand guignol (that’s Frenchy for grindhouse), a naturally dark fable that he has for years leavened with a steady patter of hillbilly yuks and heroic ass-kickings. All of Powell’s usual vile humor is on full display in these pages, but beneath them is something unexpected, something edgy. It’s there in the first panels of the fourth chapter in this book, in an outburst of comic violence that is, disconcertingly, not entirely comic. It’s there in the middle of that same chapter, when The Goon settles into his new ride alone, to take a long, anguished drive down Lonely Street. I figure it won’t ruin anything for you if I tell you the end of this graphic novel is no end at all, but the beginning of something bleak and wonderful. After a decade of entertaining the hell out of his readers, it’s clear now that Powell was only just getting started.

One other thing. The monthly edition of The Goon includes a letters column in the back, just one more way it’s a throwback to when a drugstore would sell you a comic for a dime. There was a letter to be found there, from a kid whose family had moved suddenly to Alaska, and who—in the heart of a sunless, friendless Yukon winter—came across The Goon. He wrote to thank Eric Powell, simply, for giving him adventure and a reason to laugh when he was feeling desperate for both.

I relate. I’ve never been so low or felt so defeated that a few issues of The Goon couldn’t pull me back out of my own head. When anxieties pile on like a rabid horde of diaper-wearing zombie babies, The Goon is there to throw one giant Jack Kirby uppercut and send them flying.

In an unhappy world, this is a good thing, maybe the best thing a work of the imagination can do: provide you with a vehicle, a smokin’ Roadmaster, to carry you away from the frozen Yukon of the bad times and off into astonishing new country, a place both familiar and unknown, where the possibility of a glorious two-fisted triumph over wickedness is only a few panels away. Climb in; sit down; and enjoy the ride. You can trust Eric Powell to steer you true, and take you where you want to go.

Joe Hill

New Hampshire, December 2008