Scott Green, Ain't It Cool News reporter and reviewer, interviewed Philip Simon, Dark Horse's editor for the critically acclaimed Eden manga series, in mid-September. Here's a slightly different version of that interview, prepared exclusively for darkhorse.com.

Scott Green, Ain't It Cool News reporter and reviewer, interviewed Philip Simon, Dark Horse's editor for the critically acclaimed Eden manga series, in mid-September. Here's a slightly different version of that interview, prepared exclusively for darkhorse.com.

SCOTT GREEN: Could you explain the role of an editor in the publication of a localized manga? How would you characterize your interaction with the manga's creator, its translator, and its letterer? What aspects of the release are your responsibilities?

PHILIP SIMON: A manga editor's duties can differ a bit from book to book, company to company, and even editor to editor--and some editors have assistants who share the workload. I recently started working with an assistant, Ryan Jorgensen, who's been helping me stay organized and on top of deadlines. You can probably take a guess at some of a manga editor's responsibilities, like proofreading, copywriting, rewriting scripts . . . but there's much more, and a manga editor's duties are often different from, say, an editor on Conan or Sock Monkey. What all Dark Horse editors do share in common is that we act as focal points for problem solving and as conduits for information throughout all of Dark Horse's departments. We're colorful project managers, spearheading teams that strive to make the best books possible. Whether it's a manga series or a creator-owned monthly or a custom comic for a baseball team, an editor is a part of the project from start to finish. When work begins on most of our manga series, "start" would mean finding a title that gets us fired up and gets the approval of our publisher. Then the negotiating of licensing and contract specifics can begin between Dark Horse and the work's original publisher in Japan. Our Director of Asian Licensing, Michael Gombos, can speak, read, and write Japanese fluently, and he's in charge of company-to-company negotiations, especially initial contacts and working out manga contracts. Editors can certainly chime in with suggestions, questions, and concerns, but Michael gets all of the initial paperwork squared away. Some of a manga editor's responsibilities include shepherding in materials for our letterers, designers, and pre-press staff, knowing what to ask for in order to get the best print reproduction possible, hiring the team that translates and letters the book, and getting all the in-house paperwork rolling to set aside a budget that gets everyone paid. So . . . a project gets started . . . all the paperwork's in and signed . . . I let the translator and letterer simmer and cook . . . and before I can say "Sivasubramanian," I'm busy proofreading lettered story pages and planning out the rest of the book with David Nestelle, Eden's designer. I have the most fun, as Eden's editor, fine-tuning scripts, proofreading newly arrived English-language pages from our letterer, writing ad copy and book copy, and communicating with those closest to the project--the translator, letterer, and designer. After a manga volume's proofread several times by the editor (and once or twice by our in-house proofreader, Rachel Miller), someone in our pre-press department (usually my pal Rich Powers) finalizes every part of the book digitally before it's sent off to our printer. That's just a super-quick editorial rundown. Each manga series, and actually each new comic-book series, reprint volume, graphic novel, or fine-art collection, calls for different problem-solving skills.

BUT, as manga enthusiasts know, it all really starts with the Japanese creator on a different continent, his or her hard work to bring a story to life, its serialization in a Japanese anthology, and its subsequent life in tankobon form (what we call a trade collection or graphic novel in American comics). In our constant search for new titles, we'll go through tankobon samples that we've received from Japanese publishers, we'll watch for new titles in monthly Japanese anthologies, and we'll ask our Director of Asian Licensing, Mr. Gombos, to make some calls and hunt down new projects for us. Or Mr. Gombos will bring in a series that he's read and enjoyed in its original form. We get great manga suggestions from Dark Horse fans that write in to us or leave message board comments, from convention meetings and panels, and from other Dark Horse staffers who may work outside of editorial but are ravenous manga and anime fans. Our publisher, Mike Richardson, may bring in a creator or a series that he's passionate about. Or it might begin with a creator approaching us directly, as was the case with Seiho Takizawa's Who Fighter collection. Mr. Takizawa's sister, also his agent, approached Michael Gombos at a convention. Mike Richardson was already a fan of Takizawa's war-themed manga volumes . . . and that was that. Mr. Gombos secured a contract, and I requested materials, checked digital files against the Who Fighter tankobon, asked for more art files, and then got everything else we needed, INCLUDING the original painted cover--yes, the original piece of art mailed to Dark Horse from Takizawa himself! Having the original cover art in-house will allow us to print the most faithful cover reproduction possible. Color reproduction is another thing that an editor thinks about, and it's something that a co-worker in our production department helps with. In Eden's case, my guru in production is the ever-patient, unsung hero Ryan Hill (who just got sung). Ryan double-checks the quality of our digital files, both the original ones received from Japan and the English-language ones that come from our letterers. He also completes any last-minute retouch work and lettering corrections that may be needed before the book is sent to pre-press for the aforementioned Rich's powerful finalization of files.

I've been incredibly lucky with Eden, on many accounts. When we requested our materials for translation and reproduction, a wonderful package from Japan arrived, and I immediately had quality digital files for Eden volumes one through ten on CDs. Kodansha sent over tankobon for volumes one through ten (four copies each--for the translator, letterer, editor, and design/production staff), along with superb digital files for practically every single page of each volume.

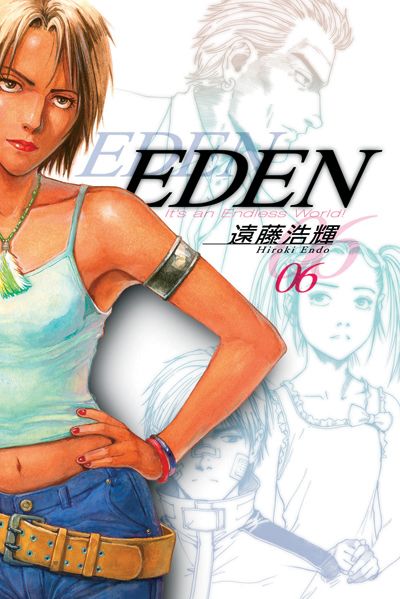

Two other accounts of a lucky editor: Steve Dutro, Eden's letterer, and Kumar Sivasubramanian, Eden's translator, because they were my first choices to work with and they were both stoked to work on Eden. As far as the communication question (that Scott asked so long ago), these gentlemen could not be any easier to work with. Kumar turns in amazing scripts, way early and crazy researched. Plenty of notes . . . he'll explain every cultural, historical, and religious reference. Kumar lives in Australia, but sometimes we'll time things just right and e-mail back-and-forth, discussing the volume we're developing and Hiroki Endo's Eden saga in general. And now--Hiroki Endo's Tanpenshu. Kumar and I are working on a handful of entirely different books . . . with Kumar translating Hiroki Endo's Eden series and the two-volume Tanpenshu anthologies, Toru Yamazaki's Octopus Girl gore-fest, and Hiroaki Samura's Ohikkoshi one-shot collection. I'm working with Steve on Eden, Tanpenshu, Banya: The Explosive Delivery Man, Shaman Warrior, and Who Fighter. I feel that Kumar and Steve make a great "one-two punch" team, because they're either way early or right on time with quality work and they communicate well. I enjoy bringing Endo's harrowing, deep world to new readers. My interactions with Kodansha have been great, and I truly believe that our translator and letterer are the best possible fits for this series. The only thing I'd ask for would be to be able to talk with Mr. Endo one-to-one. You know, to be able to just call him up and say, "Okay, turn to page 129 and explain something to me, please." Maybe he knows English and will call me up when he reads this. Maybe by the time I finish this interview he'll know English. I'll try to keep my answers shorter from here on out.

SCOTT: When localizing a work like Eden that features a cast with distinctively diverse nationalities and backgrounds, what decisions go into giving the characters their voices? What decisions are made in terms of colloquialism, contractions, and vocabulary?

PHILIP: Character-specific questions and decisions on style will begin to take form in Kumar's reading/research/translation process. When this English-language project began, Kumar read through Eden volumes one through six just to prepare for his translation work on volume one. He really does a lot of research and advance reading, and he does both online research and nice, old-fashioned library research. I believe he's read all of the Eden volumes that exist now. If anything culturally, politically, or religiously significant comes up in a script, I'll either get an enthusiastic e-mail while Kumar's translating the volume or I'll read a long note in his translator's script--which may prompt a discussion between us to clarify something in the script or in a footnote. And I do like using notes in our volumes whenever possible, both to flesh out Hiroki Endo's world and to explain important meanings behind names, scientific expressions, political forces, and other Eden-specific terms. But when you ask about "decisions" . . . for the most part, Kumar and I let Mr. Endo's original work make all of the decisions for us. With Kumar reading far ahead, he's aware of certain consistencies and verbal mannerisms that need to be present from start to finish . . . or from a character's first appearance to horrible (and hopefully--mercifully quick) death. Also, I feel that I'm good at spotting a voice that doesn't work or has "slipped up" in the rough draft of a script. I may be oddly sensitive to this issue, actually, from being a South Louisiana Cajun who was appalled by the supposed Cajun voice of the super-hero Gamit (and, as years passed, the consistent skewering of the Cajun accent in film and television). As a kid reading X-Men, I was tormented by Gambit's terribly unimaginative and un-researched "accent," which I'm sure most of the United States didn't flinch at. It just wasn't right. Month after month it wasn't right. You can't just grab a few regional cliches and sprinkled them throughout years of monthly comics! So I'll try to make sure that we don't overdo or overuse any accent in Eden, though that issue really hasn't come up yet. Dark Horse Manga editor Tim Ervin has a tougher time of it, up in the Hellsing penthouse suite of the Dark Horse offices. He's certainly doing a great job with a fistful of tough accents in each Hellsing volume. When I was working on the 128-page Super Manga Blast! monthly anthology, we had an interesting thing going with Makoto Kobayashi's Club 9 character, Haruo Hattori. Haruo's rural Akita Prefecture accent was used throughout the Club 9 series. Early on, when the translation and rewriter team of Dana Lewis and Toren Smith first began the series, they decided to give Haruo an American country (or "hick") accent. Their solution to conveying a deep rural Japanese accent was to give the character an "American country gal" accent that would contrast with the rest of the "straight English" dialogue in our translated version. Throughout Club 9, other characters react to Haruo Hattori's distinct voice, so a consistent, different accent was called for. And it works for Club 9, which is a romantic comedy. A softer touch would be called for in Eden, due to its serious nature. If Kumar recognizes a distinctive character voice or expressive flavor, our goal is to try and convey that flavor without being unimaginative, repetitive, or heavy handed.

SCOTT: Dark Horse has carried notable distinction in how well it has handled illustrated sound effects. Endo uses an extensive vocabulary of sounds in Eden. All the different machinery, gunfire, and point of impact have their own sounds. Also, the Japanese language itself is far-reaching in its words to describe sounds. A friend of mine once teased a Japanese instructor by asking for the Japanese word for the sound made by a giraffe eating grass. Besides the visual aspect of working with the sound effect illustration, what work needs to be done in adapting sound effects for a manga like Eden?

PHILIP: I take sound effects very seriously. So seriously, that we'll have to revisit this question around Eden volume ten--to check out the job we're doing and to see what I've discovered working on a series that does indeed have such a large palette of sounds. I've enjoyed sound effects as a comic-book reader, and I take great pleasure in being part of the team that now "composes the sound-effect score" for each Eden volume--and for any project, for that matter. The only thing keeping me from digitally lettering stuff myself is a lack of free time. (Just kidding, Steve--but I am fascinated by the different choices that are made when localizing different manga and handling sound effects.)

When I sit down at the computer to edit and polish Kumar's translated script, I have all of the English-language Eden volumes on hand, the original Japanese volumes on a shelf next to me, AND I have the entire Dark Horse Manga library right down the hall to refer to and draw inspiration from. Sometimes I'll look at the decisions Tim Ervin or Carl Gustav Horn or Chris Warner have made in volumes that they're working on, and I get ideas and draw inspiration from what they've done in their books. With Eden, we try our best to create (or "recapture") the right sounds, like the array of weaponry and machinery noises or the wet sounds of Kenji's knife attacks or the distinctive "chatter" of the creepy Aeon soldiers. I pay attention to katakana and hiragana in each Japanese volume, and I'm learning to spot certain sounds in Japanese without having to pull out my "cheat sheet." Another aspect of sound effects in English-language editions is how the editor chooses to present them. All of Dark Horse's manga editors are very passionate about the way they handle sound effects in each of their books, and we all have different preferences, depending on what the book calls for, of course. Another great part of working at Dark Horse is that each editor has the freedom to do what he or she feels is best for the book, within reason. I think (I think, I think) that I was the first Dark Horse Manga editor to use the "subtitled" effect of putting an English-language equivalent of the sound very unobtrusively near the original katakana or hiragana. Based on online and fan-to-editor convention feedback, that seems to work great for Eden, and I've found that that's the style that has worked best on the manga and manhwa titles that the editorial gods have blessed me with.

SCOTT: When working on a manga and deciding how to present it to a North American audience, how much attention is paid to the context of the original anthology in which the manga is published? There have been cases in which publishers have had to deal with strong content that pushed what a given manga typically dealt with, but which was in keeping with what is typically found in the manga anthology. Generally the issue has been with manga from seinen anthologies, like Eden's Afternoon.

PHILIP: My perception of Afternoon: it's an anthology that prides itself in letting a creator evolve and tell any kind of story he or she wants to tell. That "evolution" applies to the creator's artistic style as well as the mood and intensity of the series in progress. I've worked on . . . let's see . . . eight titles that have originated in or are still running in Afternoon: Eden, Hiroki Endo's Tanpenshu, Blade of the Immortal, Seraphic Feather, Shadow Star, Gunsmith Cats, Cannon God Exaxxion, and Oh My Goddess! I feel that I've seen firsthand the diversity inherent in Afternoon. That being said, when asked to look at the "context of the original anthology in which the manga is published," I'd say that Afternoon has an admirable, wide array of talent and tales, and it's a magazine that allows creators to grow and evolve. With any creator in such an exciting position, mature content may roll up from time to time as their story evolves for years. Consider the stylistic evolution in Oh My Goddess! and the content evolution in Shadow Star. Afternoon, like many Japanese anthologies, would not be afraid of what we'd call "adult content," but of course Japanese societal boundaries for such exploration in works of manga and cartoon fiction are not America's boundaries.

SCOTT: Eden appears to be a work where the small details are significant in building the larger picture. How to you safeguard against being imprecise in aspects that may become more import as the series progresses? The series' Japanese release is more than ten volumes ahead of the North American release. Do you follow what is happening in the more advanced volumes? If you do go ahead, is there the concern that advance knowledge might slant the way things are presented?

PHILIP: Kumar's read ahead quite a bit. I think he's read all of the first ten volumes. I look ahead in Afternoon because I just can't help it, and I've been very disturbed by what eventually happens to some of the characters. Something that happened this past year (in a current episode of Eden that was published in Japan) had me, literally, on my knees in denial. I was loud and probably disturbing a few of my cubicle-neighbors. When I see a character that I "know and like," I'm relieved to see them still running around in Endo's harsh world. A few things happen very soon . . . in Eden volumes four and five . . . that will have readers grabbing and re-reading volume one. Even in the quiet moments of "Twenty Years Later," when we meet Elijah in volume one, Hiroki Endo is planting plot seeds.

SCOTT: In a past review, I compared Eden to the thesis of Karen Armstrong's "The Great Transformation," which called 900 B.C.E. to 200 B.C.E an Axial Age that gave birth to the major modern religions. Armstrong suggests that the level of violence at that time reached a tipping point which directed the great minds to reevaluating their world view, which led to religious innovation. Eden paints a picture of a partially depopulated, exceedingly and starkly violent world and its protagonist engages in a spiritual progressing of the world around him. In your view, do you find that Endo is linking violence to metaphysical thought? Or, how much of this is incidental? Is there a fascination with violence and harsh subversion of action conceits and metaphysical examination without a direct, specific relationship between the two? Have you undertaken any topical research in order to handle the serious religious and technical discussions in Eden?

PHILIP: I look forward to the connections and theories and essays we'll be reading as Eden unfolds, either during the series or when it ends . . . if it does end. When thinking about Eden, as the story progresses and certain themes circle around, I find myself looking back to previous volumes for some important keys. I keep in mind obvious things that Endo has given us--like the subtitle "It's an Endless World." Endless ways to ponder a greater being and our afterlife and mankind's failures. Endless quests for redemption and endless wellsprings of hope. The endless struggle to survive, too, on different scales. Evolution on a grand scale, with global upheaval. Evolution of the "self," seen through small, personal moments and gradual shifts in character. Seeing the variety of cultures, races, and religions already present in Eden, it feels that Endo's casting his net wide from the get-go, firing off a barrage of symbolisms and commentaries on global politics (kinda like the frequent barrages of violence that titillate us so), and we're really only at the beginning stage of processing his work.

I also feel that I learn a lot from Endo's "Afterwords," that run in every book, however non-sequitur they may seem. I think his afterwords from volumes one and four have enlightened me the most about his work and where Eden might be headed.

SCOTT: Are there any scenes in Eden that affected you more acutely as the work's editor than they may have if you were just a reader?

PHILIP: I admire (and keep going back to) Hiroki Endo's entire "Twenty Years Later" chapter, which culminates with the dead boy getting buried with that little toy. That's still my favorite chapter, possibly because of the rawness and sadness of the entire situation. It's a perfect follow-up to the chapter before it, and I like how it begins very quietly, with the world empty (or, well, emptier) yet flickering with hope from young Elijah. It's refreshing to read, at first, after processing the longer, information-filled Chapter One ("Prologue") . . . and then it takes a grisly turn. I'm particularly drawn to Eden volume one, pages 144 to 150-Elijah's conversation with Cherubim as they bury the body and then Elijah places the little toy with the dead child before they cover him up. It's such a solid, human moment. A brief moment that--BOOM!--comes back to shake us up at the end of Eden volume four. And without getting into what I personally think it means or signifies (but I really do want to hear our readers' thoughts), I keep on putting the last page of Chapter Two ("Twenty Years Later") next to the last page of Chapter Nineteen ("We're Never Wrong"), where Endo forces us to compare Elijah's life with Kenji's life, as the two young warriors ponder the same thing: "If I were God . . . "

--Scott Green and Philip Simon