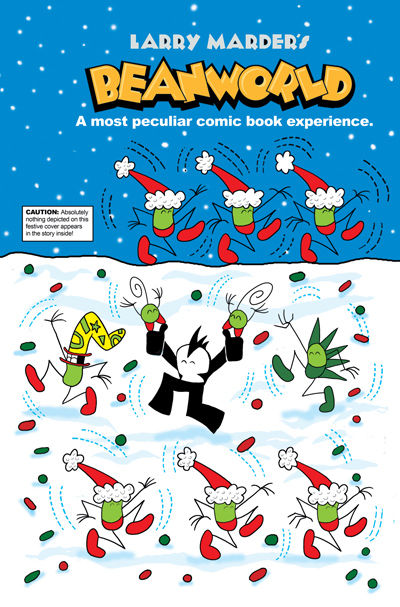

Dark Horse has always published material different from the standard tights and cape story. We often release titles that are, quite frankly, odd. We believe that the medium of sequential art is an infinite canvass for artists to create. It’s with this in mind that we’re proud to present Beanworld.

Dark Horse has always published material different from the standard tights and cape story. We often release titles that are, quite frankly, odd. We believe that the medium of sequential art is an infinite canvass for artists to create. It’s with this in mind that we’re proud to present Beanworld. Larry Marder’s Beanworld isn’t so much a comic as it is a place. Well, it’s not so much a place as a state of mind. Or maybe it is a place, but it’s a place that exists in your mind. But, it also exists on the pages of the book. So, when reading Beanworld it’s more of an experience than a story. I think . . .

Dark Horse: How did you start creating the environment and characters for Beanworld?

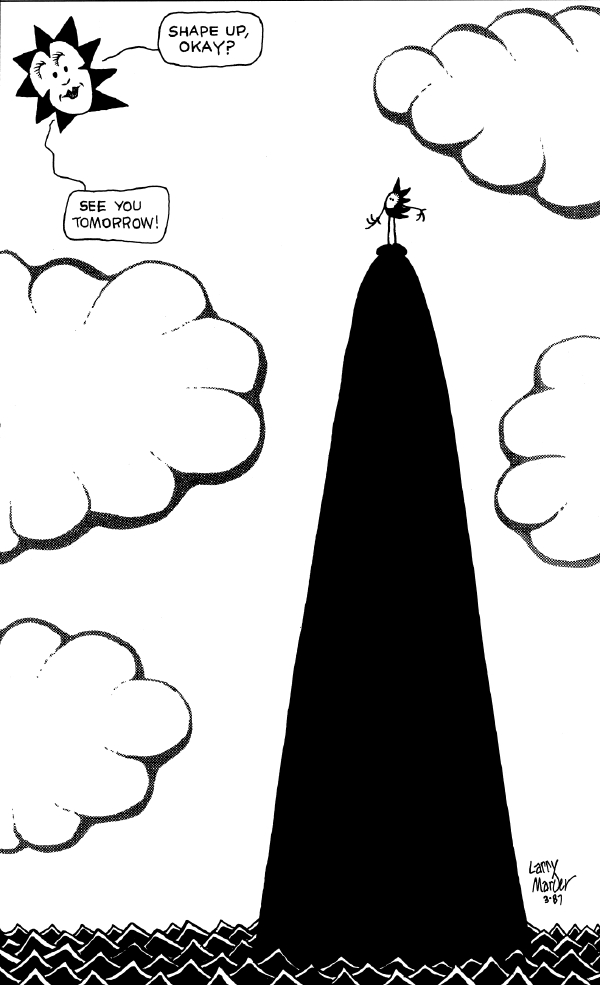

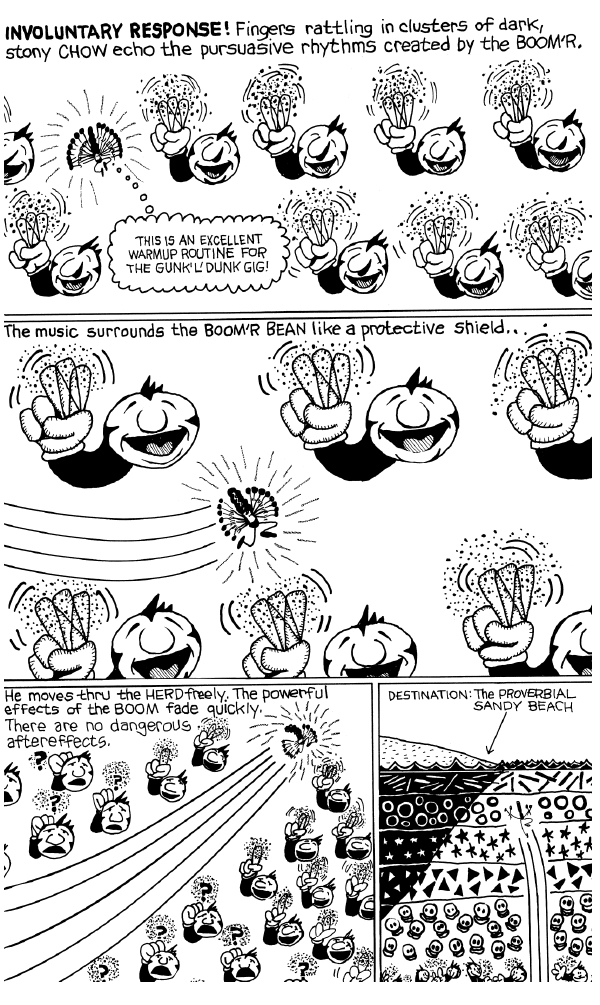

Larry Marder: Slowly. The first thing I developed was the simplicity of the basic Bean shape: the lima bean body, the little spindly arms, legs, and fingers, and the big bozo-ish feet. Over time versions of that simple character evolved into the Chow Sol’jer Army. The next character that came along was a Dr Strange-like, wizardly Bean that eventually became Professor Garbanzo. She is Beanworld’s thinker and toolmaker. Mr. Spook came along at about the same time, but he took far longer to develop as a character. He didn’t really become fully formed until I discovered the Hoi-Polloi as the Bean’s great adversaries who are also inextricably linked to the Beans as custodians of the Beanworld food chain and economy. For a long time it was as if I was sorting pieces of a jigsaw puzzle with no picture on the box to follow. I didn’t even know if I had all pieces I needed yet. When I found Gran’Ma’Pa, Beanworld’s spiritual guardian and the source of Sprout-Butts, all the pieces just snapped into place and I was off and running.

DH: What inspires you in terms of visual expression?

LM: Big ideas communicated with great simplicity. I was greatly influenced by a lot of the bold advertising I saw on TV and in magazines as I was growing up. The Avis “We try harder” and Volkswagen ads of the 1960s were clean, unadorned and straight to the point. Any ad that came out of the Leo Burnett shop had a big impact on me, but none more so than the Jolly Green Giant ads. Those ads made eating vegetables seem like a doorway into a hidden land of fun and sunshine.

I’m also greatly appreciative of the simplicity of primitive art, particularly art about one step above being pictograms. I love looking at southwestern cliff carvings and the crude but elegant drawings of Lakota winter-counts painted in a spiral on buffalo hide. I like prehistoric cave paintings. Also, early Christian Church paintings before its art suppliers became obsessed with architectural perspective and trompe–l’oeil optical illusions. One of my great heroes, Marcel Duchamp, called this kind of painting “retinal art.” Art to be looked at. And one of his goals was to return art “into the service of the mind.” Art not so much to be looked at as art to be thought about. Over the years I absorbed all of these influences and brought them all to my drawing board while working on Beanworld.

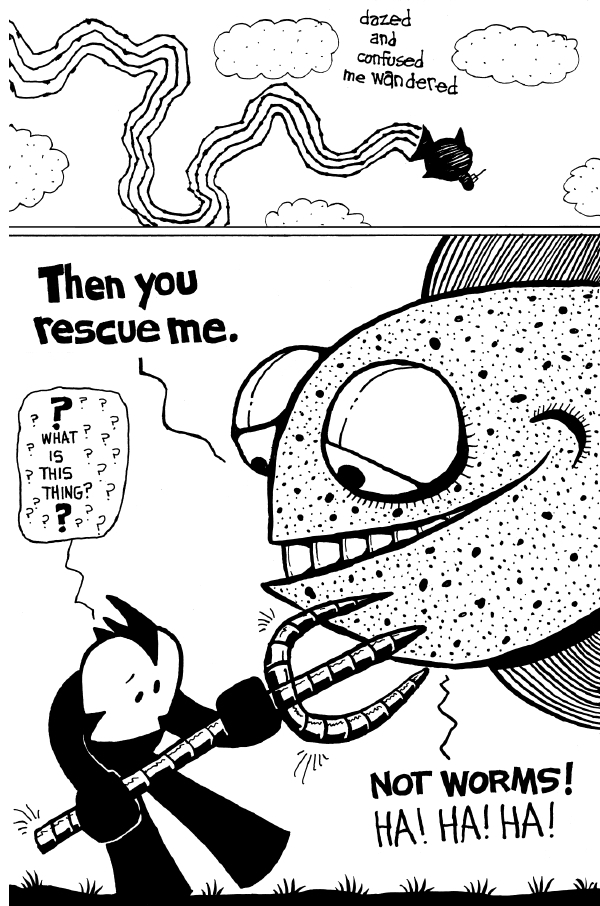

DH: You’ve stated in previous interviews that Henry Darger is one of the creators who inspired you. In what ways do you see Beanworld like Darger’s 15,000+ pages of dense environment?

LM: I can’t say that I have been as influenced by Darger’s work so much as I’ve been influenced by the idea of his body of work. When the Chicago Reader ran an article about him after he died in the ‘70s I was greatly moved by the narrative of his life. The very idea that he had worked for 50, 60 years on this cosmic, religious epic of so many thousands of pages and paintings and then never seemed to have ever actually shown it to anyone just blew my mind to pieces. When he became so infirm that had to go into a nursing home, his landlord discovered all this work in the shabby clutter of Darger’s one room apartment. He asked Darger what he wanted done with this enormous quantity of work. Darger said he didn’t care. He was done with it.

Whoa! That left me awestruck. He had daily interaction with his heroines, the Vivian Girls, in the Glandeco-Angelinnian War against child slavery, for the entire span of his adult life and now that he was going to die, he was done with it and didn’t care what happened to it. You gotta remember that had painted these long sweeping dioramic scrolls in his tiny apartment -- scrolls so wide that he couldn’t unroll them and look at them when they were finished.

Darger influenced me because I have been afraid at certain times in my life that I might risk turning into a crazy person like he was. At some point it became important for me to try to find an audience for my work.

DH: Scott McCloud has used your work to show how comics are a medium and not just a genre of superheroes. Was it your intention to use Beanworld is this way, or was sequential art simply the best format to tell the story?

LM: The comics medium seemed like the most appropriate vessel in which to pour the stories I had peculating inside me. During the ‘70s I struggled trying to figure out Beanworld wanted to be. I experimented with straight prose, illustrated stories, children’s books, performance art with giant, poster-sized-interlinked-drawings used as springboards to act out the stories going on inside the pictures. When I drew Tales of the Beanworld #1, I’d never drawn a sequence of comics that was more than a handful of pages, and most of that stuff made little sense. And then one day, it all connected and I sat down and I tried to figure out how to draw a comic book story with a beginning, middle, and end.

DH: Speaking of story, is there a plot to Beanworld, or is it more a window into a place?

LM: I stated it right on the inside of the first issue of Beanworld and every issue since. Beanworld isn’t a place, it’s a process. Sure, Beanworld is an artifact of my life, but then it is read by someone else and they, in turn, make their own Beanworld inside their own imagination. Their Beanworld isn’t my Beanworld; it is their Beanworld. I do believe my ad slogan for Beanworld is indeed a true statement. “It is a most peculiar comic book experience.”

DH: Many people have pointed out that the characters in Beanworld are dependent, in one way or another, on each other and their surroundings. Do you think this is a concept that is more relevant today than ever before?

LM: I think it has always important to understand how interlinked everything in the world actually is. The idea that some human activities are totally independent of the natural world has struck me as absurd since I was eleven-years-old. Everything that exists in space and time sure seems to be connected to everything else in space and time. Nothing is really isolated. And as a result, in nature, of careless or arrogant human behavior everything is but a few blunders away from making a big ol’ mess out of everything else. Do I think that is a good thing for people to think about? Yeah, I do. But I hope in Beanworld stories those views are just part of the subtext of ideas echoing along with many other notions I’ve stirred into the stew.

DH: Is there an underlying theme or idea that you try to guide through out Beanworld?

LM: Not really. I just try to stay out of Beanworld’s way when I sit down to cartoon. Beanworld knows far better than me what it is supposed to be. Anytime I try to guide it into a direction that it doesn’t like, it pretty much grinds to a halt until I find my way back onto a path that Beanworld likes. I know this sounds crazy but it is really true. I often feel like I am channeling Beanworld from someplace else.

DH: Diana Schutz is your editor here at Dark Horse, how has working with her shaped your idea of the series?

LM: She is an incredible editor. Working with Diana has been a dream come true. I have long admired the exceptional work that has come out of Diana’s office at Dark Horse. Diana knows when to dig in and when to let go. She has been a big supporter of Beanworld since 1983 when it was just a photocopied fanzine. I sent her free copies because she had a letter printed in the Cerebus lettercol with her full address. Diana wasn’t quite a pro yet either. She wrote me back and made some insightful observations. I’ve trusted her judgment and taste ever since. But we’ve never actually worked together until now. The Dark Horse art and production crews under Diana’s watchful eye have really captured the loopy feel of Beanworld. Next year’s hardcover book “Wahoolazuma!” is a very handsome deluxe 272 page package at an incredibly affordable price of $19.95.

DH: Do you have a favorite character in Beanworld?

LM: I really don’t. I seem to like whichever character I’m drawing at that moment. But that said, Beanish, the creator of the Fabulous Look-See Show, is probably the one character most like me.

DH: If you could live in any magical realm, what would it consist of?

LM: The Green, the magical realm of the Parliament of Trees, as described by first by Alan Moore and Rick Vietch in Swamp Thing. Forgetting for a moment, a hard thing to do I admit, that The Green and the Parliament of Trees is DC Comics' intellectual property, it seems to me that from a mythological point of view, Beanworld would have tendrils that curled into the Green. Actually at the Creator's Rights Summit Conference in 1988, Rick and I briefly daydreamed about a Swamp Thing / Beanworld intersection taking place where the The Green and the Big-Big Picture touched, if not merged, for a moment or three.

And remember, the Beanworld: Holiday Special ships December 17th, 2008 so be sure to check it out!